Ancient Rome was the capital of the known and civilized world. Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire recalls the power and honor due to the City at the height of her Imperial powers:

"In the second century of the Christian era, the Empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind. The frontiers of that extensive monarchy were guarded by ancient renown and disciplined valour. The gentle but powerful influence of laws and manners had gradually cemented the union of the provinces. Their peaceful inhabitants enjoyed and abused the advantages of wealth and luxury. The image of a free constitution was preserved with decent reverence: the Roman senate appeared to possess the sovereign authority, and devolved on the emperors all the executive powers of government. During a happy period of more than fourscore years, the public administration was conducted by the virtue and abilities of Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, and the two Antonines. It is the design of this, and of the two succeeding chapters, to describe the prosperous condition of their empire; and afterwards, from the death of Marcus Antoninus, to deduce the most important circumstances of its decline and fall; a revolution which will ever be remembered, and is still felt by the nations of the earth."

Gibbon was quite gifted with adjectives. In the modern day, scholars and tourists alike remember and glorify Renaissance and baroque Rome for its humanism, its revival of painting and sculpture, its place at the center of emerging nationalistic politics, and for its romantic ambiance. This is the Rome of Bernini, Michelangelo, Sixtus V, and Urban VIII. One would think Rome was a city in eternal strife, earmarked at opposite of its history with two periods of adroit artistic and political vibrancy. The understanding of Rome is natural, intuitive, grounded in artistic history and a deep appreciation for the ancient City. It is also completely and utterly wrong.

Rome, aside from these two epochs, also enjoyed a period of religious revival, prosperity, and recovery of self-identity during the high Middle Ages. Renaissance Rome sprung forth from the fountainhead of medieval Rome, not from a vacuum of dark illiteracy and religious ignorance.

Rome entered a truly dark age after the sackings and raids of the fifth century, the abandonment by the Byzantine empire, and the waves of plague which sent most of the still-living populace into the countryside. Rule of the city devolved to the Pope, known until Pius IX as the "Lord Pope," a title used even within the Magna Carta. A form of Senate continued to run the daily, micro-level affairs of the City and the old families held some level of authority, but the Popes' spiritual and administrative power over the churches meant that the Bishop of Rome was the Lord of Rome. Unfortunately, [St] Leo III crowned Charlemagne and the various families of Italy sought the papacy so they could play king-maker and live off papal beneficences. In the 9th century, the Mohammadans sacked Rome and ravaged St. Peter's Basilica. The papacy entered its absolute nadir, when the Bishops of Rome descended from Marozia—mistress of the murderous Pope Sergius III. Indeed, six popes (John XI, John XII, Benedict VII, John XIX, Benedict VIII, and Benedict IX) came from her line, with a few elderly men functioning as placeholders in between, murdered if they lived too long.

Finally, the Gregorian reforms emancipated Rome from central Italian politics and the un-Holy Frankish Clan Holy Roman Empire. What emerged was a Rome revived in continuity with its past, aware of its present, and vivacious in faith.

Ancient peoples were not so introspective and concerned with documenting their own ways as we are today. One is often struck by the absence of ritual descriptions or theological treatises on non-Scholastic during this age. The ancient and medieval Christians expressed what they believed in what they did, not in word alone. They manifested their Roman tradition of faith in their church and secular architecture, as well as in their liturgical and artistic endeavors.

Roman art during the Middle Ages derived from the older Roman mosaic tradition. While the Orthodox Greek tradition had long ago transitioned into painted, "written" icons, less and less realistic in their appearance, the Romans, a people averse to change and innovation in religious matters, kept their mosaic tradition and even imported it into new places. The below mosaic outside of Santa Maria in Trastevere looks quite ancient, but in fact dates to the 12th century.

|

| source: wikipedia |

Unlike the Norman French and English, who built their new churches along the soaring vertical lines of gothic pillars and arches, the Roman people conscientiously kept in continuity with their received identity and tradition in all matters, especially architecture.

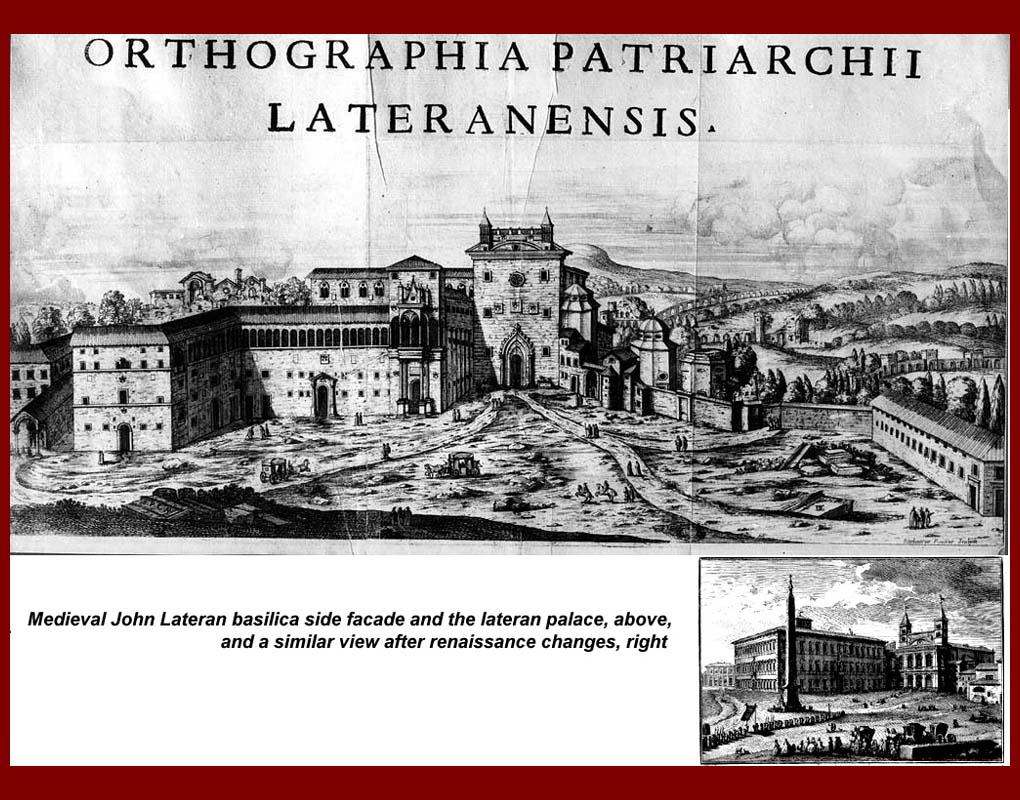

Between 1198 and 1216, one of the great men of the Middle Ages, Lothar Segni, sat atop Peter's chair. Keeping with his own doctrine of the spiritual power's place over the temporal power, he refitted the Lateran palace for the government of the Church and as an example to the world. Sadly, few if any records or reconstructions of the ancient Lateran palace exist for us today. Dante called the Lateran palace a place "above all earthly things." Below are two rare representations of what the palace and adjoining cathedral looked like prior to the tearing down of the palace and the addition of a baroque facade on the Archbasilica.

|

| source: mmdtkw.org |

|

| source: augustineofcanterbury.org |

These views are from the north, not the front entrance to the cathedral, which is to the east. The Lateran palace, built by the Lateran family and given to the popes by Constantine, encompassed a large courtyard—a feature of Roman palatial architecture imitated with the building of the Apostolic palace adjacent to St. Peter's basilica and the new Lateran palace. Until the 9th century or so, the popes were elected by the people of Rome in the field in front of the cathedral. Often violence would break out and whoever won control of the Lateran complex became pope. This author once recalls reading about a victor having difficulty convincing the mob to spare his opponent's life. Next to the courtyard, at the upper left of the above picture, was the Triclinium of Leo III where Innocent III held the fourth Council of the Lateran. This remarkable hall was torn down, its former foundations replaced by roads. Its apse still stands tall in memorial to its previous function.

|

| source: wikipedia.org |

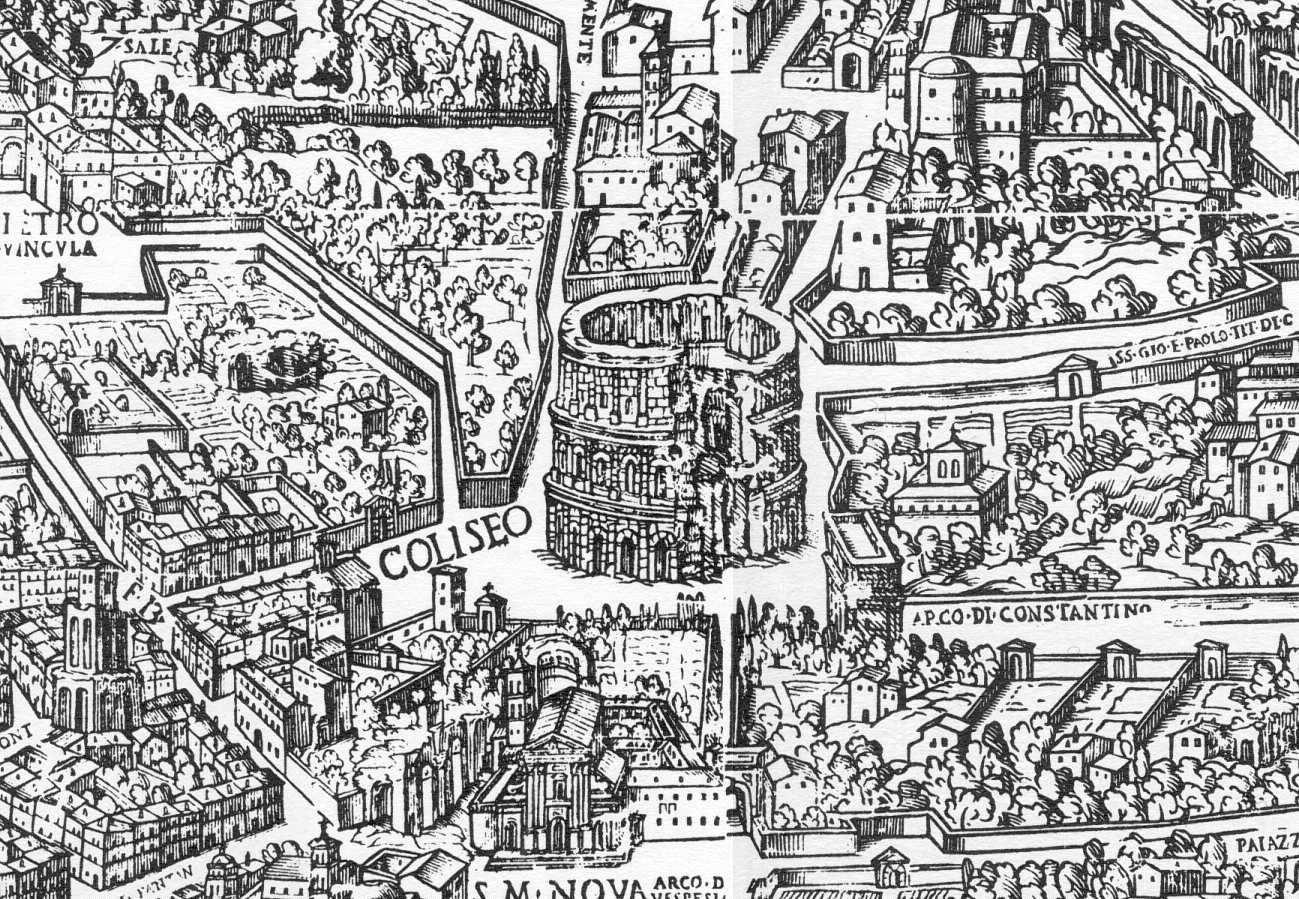

The revival of education in France and trade with the East incited by the Crusades brought Rome back to significance in the intellectual and economic realms, attracting students seeking theological knowledge and merchants looking for middle-points in their routes of trade between the Continent and the Eastern Mediterranean. The Colosseum returned to use after half a millennium of dormancy as an open market and, what we would now call, an industrial park.

|

| The Colosseum during the Middle Ages source: wikipedia |

Above all, the Romans still realized that they were the ancient City that ruled the world and that they were now, without contradiction, the City that ruled the Christian world. As such, Rome revived many of its more catholic Catholic features. The early praxis of reading the lessons of the Mass and Office in both Greek and Latin returned, as did use of the stational churches by the Lord Pope on great feasts. The ancient, un-gallicanized rite of Mass remained in use by the pope one day a year on the feast of St. Peter's Chair in Rome. This ancient use involved numerous deacons and subdeacons, long psalms instead of simple chants, no offertory or silent prayers, a sung Canon, and concelebration. The Lateran and Vatican basilicas also retained the ancient Divine Office, which uses the same orations, antiphons, and psalms as the pre-Pius X Office, but sans introductory rites, no hymns, and a more communal ritual. Moreover, the canons recited the Offices of the Dead, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and of All Saints on ferial days per annum and provided pastoral care to the great many pilgrims. Innocent III himself was a canon of the Petrine basilica before his election and familiar with the observances. These rites remained in use until Franciscan pope Nicholas III squashed everything not done in the Franciscan Order. The Byzantine monastery in Rome also enjoyed a resurgence, with no less that six hundred monks and priests in residence in the 12th and 13th centuries. This also suggests that the Rome-Constantinople schism was not taken as seriously during this period as it would be after 1453. The clergy and people of Rome were the enemies of streamlining. Far from assuming the Church required one way of celebrating Mass, as the capital of Catholicism, they welcomed the catholicity of rites practiced within the City.

Medieval Rome was not the superpower ancient Rome was, nor was it the artistic center baroque Rome would be. But it was once again alive and acting as the center of the Christian world. Perhaps this is why modern historians are unable to see that the period between the Gregorian reform and the Avignon papacy was a glorious one, because they cannot understand how Christianity can be the lifeblood of a people.

|

| Rossellino's proposal for the new St. Peter's basilica source: studybluecom |

Then came the Renaissance. Much would have to be lost and rebuilt because of the neglect of the popes while they lived in Avignon. St. Peter's basilica is particularly flagrant example of the paradigm shift. The roof on the old basilica was wood needed regular replacement, something ignored during those dark French years. As a result, the roof collapsed, fires occasioned the church, as one of the walls warped out by six feet. The basilica, built 1,100 years earlier, was beyond saving. Bernardo Rossellino proposed a new basilica built in the same style and with the same features as the old church, only with longer transepts to accommodate devotions and a longer choir for the new, medieval choir praxis. His proposal was canned by Julius II, who wanted a grand new church to house his tomb. Bramante began the construction of the modern basilica, a significant departure in style and outlook from the previous building. With the new basilica, Pope Julius baptized Rome into the Renaissance and gave precedent for a severe remodeling of many churches of the City along new lines. Rome became a center of baroquerie and its old identity began to fade. Lex supplicandi legem statuat credendi.

|

| The old basilica, along with Cluny and St Paul outside of the Wall, the largest church in the world, is demolished and covered with the new basilica. |

Medieval Rome is gone, but we ought not forget how wonderful a Catholic city it was nor should we neglect its example as a city conscientiously dedicated to God.

Thank you for the very informative post. Can you give us the source you were using?

ReplyDeleteIn the good 'ole days, the monks spent 8+ hours a day chanting Holy Mass, the Roman Office, the Office for the Dead, the Little Office of Our Lady, the Gradual Psalms, the Penitential Psalms, Intercessions for the Supreme Pontiff, and more. It's incredible to think nowadays the Hours are barely ever chanted anymore in Rome because the Nova Vulgata is hard to sing, and there's barely any interest in the post-conciliar Office among the laity anyway.

ReplyDelete